Jerry Harris Sees Stars

Artist has created more than 1,000 portraits of country music legends

Before television, there was radio, which meant to “see” what you “heard,” you had to use your imagination.

Before television, there was radio, which meant to “see” what you “heard,” you had to use your imagination.

For a young Jerry Harris, that meant visualizing the country music performers to whom he and his family listened.

“When I was a kid, religiously on Saturday nights, we would gather around the radio and listen to the Louisiana Hayride until it went off,” Harris remembers. “Then, my parents would turn over to the Grand Ole Opry. We sat around and listened to that like you sit around and watch TV.”

Thus began Harris’ eight-decade love affair with the performers he “saw” and the sounds he heard.

“It was pure country,” said the now-85-yearold. “It told a story. You could understand the words. It was music that hit home. … Country music is all about listening to a song, and it invariably brings back a thought or memory of something you did or said, or somewhere you were.”

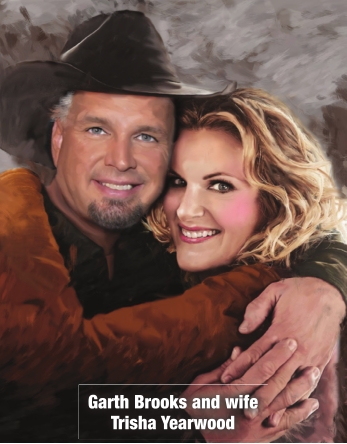

Born in Dennison, Texas, and raised in Dallas, Harris has found a way to put pictures to the music he loves. A former, long-time advertising executive, Harris says he’s drawn or painted approximately 1,000 portraits of country music legends. From his favorite, Loretta Lynn (“She’s got four of my paintings at either her house or her museum”), to Charlie Pride, to Tanya Tucker.

“You can’t name a country music artist that I haven’t done a painting of — at least one,” Harris proudly said.

Many of Harris’ subjects played at the Louisiana Hayride. From 1948-1960, the Hayride helped launch the careers of Hank Williams, Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash — just to name a few.

“I was invited to do the portraits for the museum they (the Hayride) had at one time at the Municipal Auditorium,” Harris said. “They wanted me to do the portraits of the artists how they were at the time they were performing.”

Unfortunately, Harris says, most of those 105 pencil portraits are now in the auditorium’s basement.

“They remodeled,” Harris said, “and didn’t want to put holes in the wall.”

When Harris sits down and puts his talent to work, he has one goal.

“I’m trying to improve what I’m working from — usually a photograph or something online — to bring out their features,” Harris explained. “I like doing portraits that have character in their faces. … I’m trying to bring out the best.”

However, it was “bringing out their features” that got Harris in trouble with, whom Harris says, is the only person ever to be unhappy with his work — and she wasn’t from the world of country music.

Years ago, actor Dana Andrews — a major star in the 1940s who died in 1992 — performed at Shreveport’s Barn Dinner Playhouse.

“His wife was with him, and I did a portrait of both of them,” Harris recalls. “He told me she didn’t like what I did. I got the black-andwhite picture that I took the work from and looked at what I had done. It looked exactly like the photograph. Then I got to thinking — why didn’t she like that? Then it came to me. I put all the wrinkles on her face. I said, from now on, I’m not going to do that. I haven’t had any problems since then.”

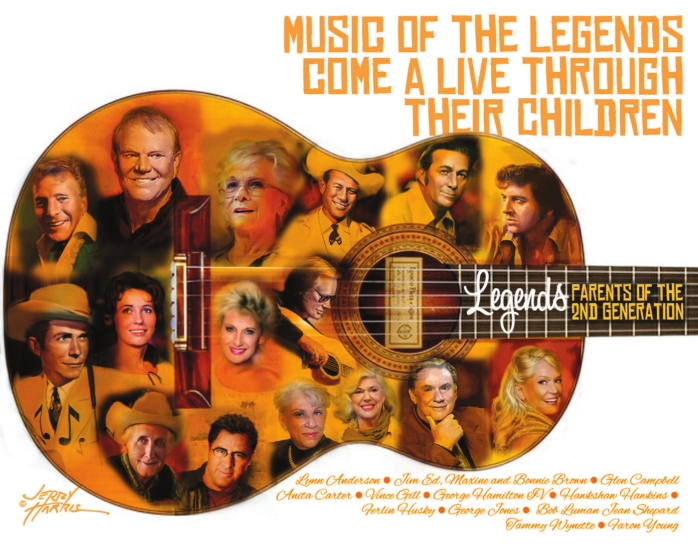

Despite his age — “Everybody says I don’t look 85, and I love to hear that!” — Harris is still active in keeping alive “pure” country music. He is working with others on a show called “Louisiana Jamboree.”

“We’re trying to make it a Branson (Missouri)-type production,” Harris explained. “I have done all the portraits of the legends — our show features the songs of the legends. We use my paintings when the songs of that legend are sung, and we project the painting of that legend on the screen, so everyone will know what he or she looks like. We do that to enhance the show and make it more interesting.”

The days of sitting around and listening to the radio are pretty much gone. But for Harris, the memories — and the music — remain.

“My whole goal is to preserve country music.”

To see some of Harris’ portraits, you may visit his gallery at 825 Shreveport-Barksdale Highway. To schedule a time, please call 868-0901.