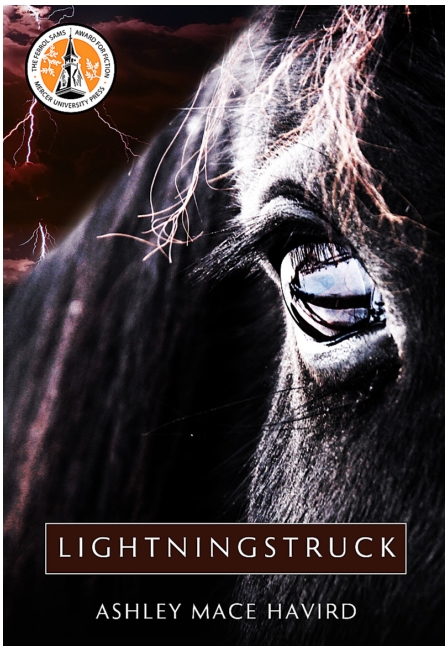

LIGHTNING STRUCK

Exhibit evokes book’s sense of place

So reads the superlative first sentence of Ashley Mace Havird’s debut novel, “Lightningstruck”. And who wouldn’t want to read further after taking in these words? It’s impossible not to wonder if the horse survived – you quickly find out it has – and why 11-year-old Etta McDaniel believes her world has turned crazy.

The first chapter of Havird’s novel fulfilled the promise of that sentence, garnering my Best of Show award in the literary competition of the Shreveport Regional Art Council’s Critical Mass 4. “Lightningstruck,” which will be published in September by Mercer University Press, fulfills the promise of its first chapter.

The exhibition devoted to “Lightningstruck,” on view at artspace through Aug. 13, offers a compelling introduction to the book. Havird has selected judicious excerpts from it as well as photographs that strongly evoke the book’s sense of place and its historical context.

Her novel is set in the tobacco country of South Carolina, where Havird came of age, and the time is 1964. In the show, the tobacco culture of the region is pictured in such enduring images as “Daughter of an African-American Sharecropper ‘Worming’ the Tobacco (1939),” by the great documentary photographer, Dorothea Lange. As insular and tradition-bound as Etta’s tiny town is, the relations between its white and African-American citizens are being altered by the larger Civil Rights Movement taking shape across the South. This aspect of the novel is represented in the exhibition by iconic press photos of that era, such as the haunting pictures of four young girls killed in a Birmingham Church bombing in 1963 and of the sit-in, that same year, at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in Jackson, Miss.

Even the small portions of “Lightningstruck” that appear on the walls of the gallery give us a sense of the compelling voice of Etta, who tells her own story. Most of us have read one classic coming-of-age novel or another. A list of enduring books in this vein would include the “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” “The Catcher in the Rye” and “To Kill a Mockingbird.” To this list I would add a recent example of note: Donna Tartt’s “The Goldfinch.”

The great appeal of these narratives is to feel as if the author is speaking directly to you. The magnetic voices in these novels pull you in quickly – and Etta’s does, too. If the question about the survival of Troy, Etta’s horse, is disclosed in the first pages of the book, the bigger question is one the reader has to answer for him or herself. Are the events in Etta’s world signs of madness? At least in some measure, the term rings true to an 11-year-old girl’s way of seeing her world. But we should keep in mind that many a boy or girl of that age has a flair for melodrama and hyperbole.

So much of the novel is anticipated and hinted at in its first chapter. There is the gap between the horse Etta yearned for and the horse she has. There are her complex relationships with Cleo, the housekeeper who has essentially raised her and whom she loves deeply; with her brother Will, who gets bullied at school for his cleft palette and whom Etta feels compelled to protect; and with her grandfather, Mr. Mac, who puzzles Etta by his low-key reaction to events that trouble her deeply. Then, intertwined with all of these bonds is her relationship to the physically damaged horse, Troy, which she resents and yet is still her responsibility. Each of these characters is richly realized, including Troy.

“Though I couldn’t put it into words,” Etta reflects near the close of this chapter, “it occurred to me that somehow the stark raving madness of the world, which has seemed for almost a year now to keep me off-balance, lived in this gruesome horse, whose one good eye, as Cleo said, was evil.”

Of course, as in all elegantly structured novels, you shouldn’t take the narrator too literally. Madness and evil are highly subjective terms and at least partly ambiguous ones, as the chapters of Havird’s luminous debut novel makes clear.

– Robert L. Pincus