TRAUMA

A Path to Destruction Part I: Hurt People Hurt Themselves

“The men were different, but it was always the same. I was in bed, and I would see this bright light shine in my eyes as the door cracked open, and I could feel my heart beating so quickly. They had always been drinking. I could smell the alcohol.”

This is the first piece in a two-part series on trauma, also known as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), and how it relates to addiction and other risky behaviors.

Media coupled with technology has made it easy to see the devastating effects of addiction and how it devastates people and their families, although most of the time, we only see part of the story. Everyone seems to have an opinion on the causes of substance use, and the accompanying judgment and stigma only exacerbate the trauma many substance users have experienced. Thankfully, there is significant research that answers the question, why are so many people consumed by drugs, alcohol and other self-destructive behaviors? Believe it or not, much of it goes back to childhood trauma.

Trauma, as discussed here, refers to extreme stress that overwhelms a person’s ability to cope, even years later. Dr. Kent Dean, director of clinical development for the Council on Alcoholism & Drug Abuse (CADA), explained: “The primary urge for all animals, including humans, is survival. Any event that threatens our survival is experienced as toxic. Our distant ancestors didn’t experience the range of trauma that can befall modern humans. In more modern times, the threat can come from many directions. Through the ages, our bodies evolved to process a steroid hormone called cortisol. In short bursts, cortisol empowers us to decisive action in the face of a threat. In longer bursts, it can interfere with the immune system. A little bit is good; a lot is damaging.”

“Traumatic stress brings about a prolonged elevation of cortisol levels and intensifies the fight, fright or flight response to stress,” Dean added. “People who’ve been traumatized can find themselves unable to recover any sense of emotional equilibrium. They seem to be stuck in the traumatic response, frequently either overreacting or underreacting to stimulation.”

The Research

Stressful or traumatic events from childhood have come to be known as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) by clinicians and educators. The CDC- Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE) is one of the largest investigations of child abuse and neglect and later-life health and wellbeing (www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/ acestudy/about.html).

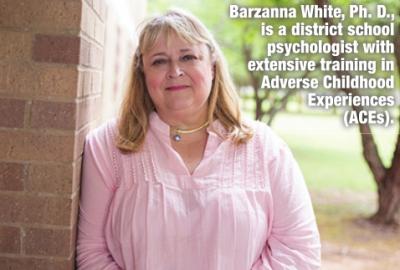

Barzanna White, Ph.D., is a district school psychologist and school climate transformation grant director who has had extensive training in ACEs. “The magnitude of the ACE study is significant because of the number of individuals studied – over 17,000 – and because it was longitudinal in nature,” White said. “It was really the first time there was scientific evidence that correlated early childhood trauma to mental, behavioral and physical problems later in life.”

Clay Walker, director of juvenile services for Caddo Parish, agreed. “It’s the science behind what I have seen for 20 years working in Juvenile Court,” he said. “It explains the biological impact of abuse and neglect. It explains small changes that all of us can make as well as larger policy and legislative changes which could improve the lives of people who have suffered abuse and neglect. A better understanding of ACEs would help our school system as well as our juvenile justice system and would reduce school misconduct and lower juvenile crime.”

Clay Walker, director of juvenile services for Caddo Parish, agreed. “It’s the science behind what I have seen for 20 years working in Juvenile Court,” he said. “It explains the biological impact of abuse and neglect. It explains small changes that all of us can make as well as larger policy and legislative changes which could improve the lives of people who have suffered abuse and neglect. A better understanding of ACEs would help our school system as well as our juvenile justice system and would reduce school misconduct and lower juvenile crime.”

“When trauma is experienced, a memory of that abuse is stored in the brain like a tripwire,” Walker said. “Encounters which remind the person of the abuse trips the wire (a trauma trigger), setting off a physical reaction as if the abuse is happening again in that moment.”

“For example, if a child is sexually abused by a family member who wore a particular cologne,” Walker said, “and then later in life encounters a person wearing that same cologne, he or she can then be reminded of the abuse. Triggered by the smell, he or she can have a panic and fear response as if the abuse were happening at that moment. The trigger can be a sound, a light, a smell or taste – anything that reminds them of the abuse. It can send the person into a fight or flight response, which could be appropriate to fight off a sexual attacker but is not appropriate in a classroom or other social setting.”

Children are often identified as having had ACEs in the court system, such as Walker described, when getting substance treatment like at CADA, or in a school setting after being labeled as having a behavior problem. “As a district school psychologist, I see numerous children who have experienced early childhood trauma,” White said. “Getting staff members and parents to understand that it’s really not a child’s fault, but rather what has happened to them early on that has resulted in their behavioral manifestations is key. Reframing your perspective to a trauma-informed perspective is important. Rather than saying, ‘What’s wrong with this child?’ think about it as ‘what has happened to this child?’” Dean described some of the ACEs reactions he’s observed at CADA. “We encounter and recognize trauma through a comprehensive assessment of the life of someone presenting for services,” Dean said. “People who’ve been traumatized present with many possible symptoms, including episodes of rage, nightmares of the traumatic event and intrusion of traumatic memories while awake, or what I call ‘daymares.’ Also, a general numbing of responsiveness, fearfulness, dissociative episodes in which the person is temporarily unresponsive to the world around them, and flashbacks to the traumatic event.”

Walker also sees the damage of ACEs every single day. “The children and families who return to Juvenile Court with continuing problems almost all show signs of trauma,” he said. “To be clear, roughly 80 percent of the delinquent children we work with don’t come back – they do not re-offend. Those folks generally do not exhibit trauma. But, the 20 percent who do come back, come back constantly. That 20 percent have early childhoods riddled with abuse, neglect, poverty and other forms of trauma.”

Susan Garcia has spent many hours in substance use treatment and counseling to help her understand how her trauma and those memories led her down a path of selfdestruction. “Just imagine being a 5-yearold that already knows something is not right with her life, that she is different – who doesn’t know who she really is or who she belongs to,” Garcia said. “By the time I was 8 years old, I trusted no one.”

The only way Garcia knew how to deal with her fear was anger. She was already drinking by the age of 12. “It helped me, or so I thought,” she said. “It made me less fearful of life in general and helped me be whomever you needed me to be in order for me to receive the attention I was seeking. I started to become a different person.”

Garcia has an inventory of traumatic experiences, and she’s not afraid to talk about them. “Neglect,” she said. “I was abandoned by my parents as an infant and then passed around living with a couple of different family members and finally ending up with my godparents by the age of 8. Sexual trauma: I experienced multiple occasions of inappropriate touching by males.”

Garcia has an inventory of traumatic experiences, and she’s not afraid to talk about them. “Neglect,” she said. “I was abandoned by my parents as an infant and then passed around living with a couple of different family members and finally ending up with my godparents by the age of 8. Sexual trauma: I experienced multiple occasions of inappropriate touching by males.”

“Traumatic grief,” Garcia continued. “My brother was beaten to death and thrown into Grand Isle when I was 14 years old. Then, my sister was killed in a wreck on the way to New Orleans for my brother’s funeral.”

Garcia experienced still another common form of trauma among women and children: domestic violence in an abusive relationship that left her pregnant at 14. “I was terrified to tell a soul,” Garcia said. “I just knew I would be kicked out with nowhere left to go since I had made my way through all my family members. I kept it a secret, and no one I lived with ever knew. A full-term pregnancy with no doctors, no nothing.”

Garcia eventually had to get help or die. “I remember the light over the operating table, and the ER doctor telling me, ‘10 more minutes,’ and I would have died,” she said. “My son was stillborn, and I completely blamed myself. I have only recently come to understand that I was a child, and someone should have noticed. Someone should have helped me.”

“I always felt unwanted, not good enough, like I didn’t fit in anywhere,” Garcia explained. “A typical question for myself growing up was ‘what is wrong with me?’ and I spent the majority of my young life trying to figure it out.”

“There is not enough discussion about this,” Garcia said. “A lot of people don’t want to talk about trauma at all, or they think people need to just get over it. It is not that simple. More conversation needs to happen in the community, and we need education about it.”

In the next issue, we will continue the discussion about Adverse Childhood Experiences. We’ll hear more of Garcia’s story, as well as find out from our experts, Dr. Kent Dean, Dr. Barzanna White and Clay Walker, just precisely what they believe needs to be done to address the destructive effects of unidentified and untreated trauma in our community.

– Susan Reeks