The green monster of Caddo Lake is in retreat.

Efforts to bring the aggressive Salvinia under control on the scenic waterway, making it inaccessible, have made tremendous progress ... and it shows.

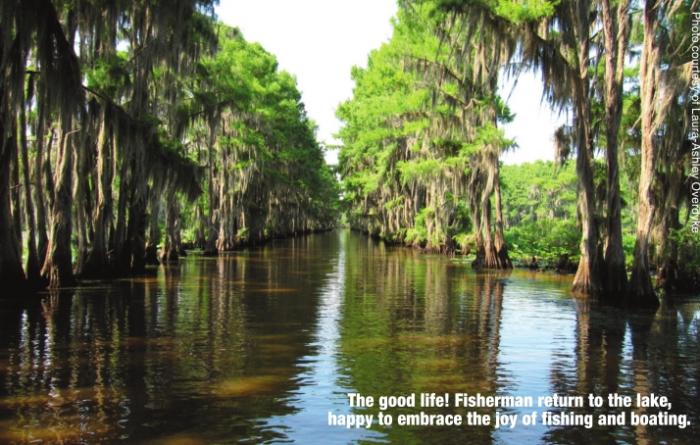

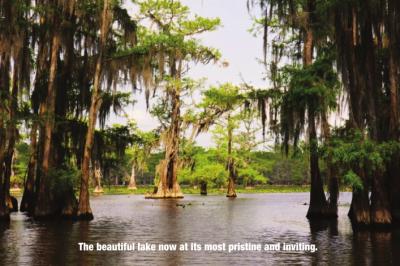

With Spanish moss draping from ages-old cypress trees, and both operational and long-abandoned oil wells rising from its depths, Caddo Lake is one of the most scenic waterways in the country.

With Spanish moss draping from ages-old cypress trees, and both operational and long-abandoned oil wells rising from its depths, Caddo Lake is one of the most scenic waterways in the country.

Not to mention its environment makes for some of the best fishing in the South.

But until recently, the beauty and the bass – in fact, the entire existence of Caddo Lake – were in danger.

The culprit?

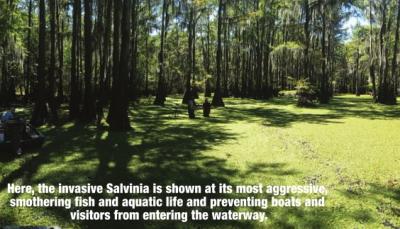

Salvinia, an aquatic plant (fern) native to Brazil which floats on water. Because of its thickness, too much salvinia can make it difficult – sometimes impossible – for a boat to cut through or a fish to breathe.

“There were a lot of people who were very concerned that salvinia was spelling the death of Caddo Lake – that this would be the end,” said Laura- Ashley Overdyke. “That we could not stop it soon enough. That it would crowd out everything else, and we would soon have a fisheries crash and an economic recreation crash where there wouldn’t be boat guides, there wouldn’t be a place to get gas – or get a bite to eat – on the lake. That those people couldn’t make it.”

Overdyke is executive director of the Caddo Lake Institute, a non-profit organization which, since 1993, has focused on issues dealing with the lake.

“It was really threatening the future of the lake,” she said.

Mike Echols has spent many a day on Caddo Lake. A longtime, avid fisherman and co-host of the “Hook’n Up & Track’n Down” radio show, remembers how difficult it was just to get on the water. One of his favorite places to launch was Tucker’s Marina.

“It put you right on top of some of the best fishing on the lake,” Echols said. But the salvinia – at its height – made going out of that location impossible.

“I remember several times we tried to launch at Tucker’s (Marina) on the southwest corner of the lake, and the salvinia was so thick, you pushed your boat off the trailer and you could not idle out to get to clear water. It was

CONTINUED ON PAGE 12

THE GREEN MONSTER OF CADDO LAKE continued from page 11

inaccessible. We would have to go launch someplace else and run 15 to 20 minutes across the lake to get back there.”

But after 13 years of fighting the salvinia – and often times losing – Caddo Lake is coming back from death’s doorstep.

(At its height), “there were probably 6,000 acres on the Texas side covered with salvinia,” Overdyke said. “At this moment, there are less than 2,000 acres covered.”

“I would say where we had 60-70 percent of the lake unfishable because of the salvinia, I would say that’s now down to maybe less than 10 percent,” Echols added.

There isn’t just one reason for the improvement. There are several:

Mother Nature

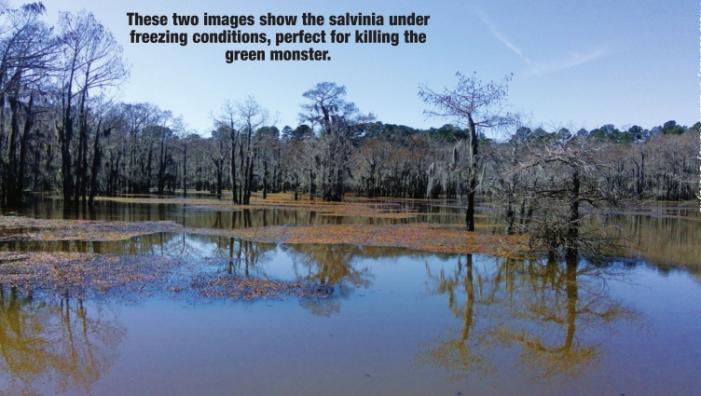

“We had hard freezes for long enough to kill off a lot of the salvinia,” Overdyke explained. “We’ve had a lot of high water, and since the salvinia floats on top, unlike those other plants that are moored to the bottom of the lake, these are the floating kind. So when the water gets high, it goes over the spillway in Mooringsport into 12-Mile Bayou and into the river, where it’s in fast-moving water and doesn’t cause problems. When it gets to the Gulf, the salt kills it. So it’s not problematic when it goes downstream.”

Aquatic Herbicides

“Texas Parks and Wildlife and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries have increased their budgets over the years for aquatic herbicides at Caddo,” Overdyke said. “The people who apply that herbicide have gotten increasingly sophisticated. They’re constantly educating themselves, they’re tweaking their application, they’ve learned what time of year – what concentration – different mixes of herbicide, so they’ve gotten very strategic – and much more effective – at their herbicide applications.”

Weevils

That’s right. Weevils. “When you have an invasive species, you go to the place from where it came, and you figure out how it’s managed in its native place – why it doesn’t take over back home,” Overdyke said. So the LSU Ag Center went to Brazil and found these weevils. They only eat salvinia. If there’s no salvinia, they starve to death.

So, weevils were brought to Uncertain, Texas – home of the non-profit Caddo Bio Control Alliance. “They have a greenhouse,” Overdyke said. “They say it’s the world’s only climate-controlled, high-production weevil greenhouse. They’ve been raising them for several years. They’ve gotten very good at raising them.”

Salvinia’s invasion of Caddo Lake likely started at another lake.

“We don’t know 100 percent how it got into Jeem’s Bayou (where it was first found),” Overdyke said. “Most people say it was a duck hunter or a fisherman on a boat that had been in a different lake that was infested. They came to Caddo Lake to hunt or fish, and unwittingly it came off their boat into Jeem’s Bayou.”

From that point on, there was no stopping the salvinia’s growth. You could only hope to contain it.

“The first few years, the locals were able to kind of keep it in check,” Overdyke said. “Then during Hurricane Ike, the wind blew it all up into the backwaters and the cypress trees and the nooks and crannies. Once the wind dispersed it into the cypress trees and the nooks and crannies, that’s when it took off.”

But there is more than salvinia for the Caddo Lake Institute to deal with.

“The Caddo Lake Institute takes a broad view of the major issues that affect Caddo Lake,” Overdyke said. “That’s primarily making sure we have enough water – which seems strange in a time of lots of rain, but when we’re not getting rain, like the 2011 drought, getting enough water from upstream – Lake O’ the Pines – to keep the forest healthy and to keep the fisheries healthy and to keep the wetland alive, has been really important. That’s probably our primary focus.”

“Our second focus is the quality of the water,” Overdyke said. “We’ve been able to monitor the water monthly for almost 20 years. We’ve seen spikes in various things, and worked with industry to reduce pollution by 40 percent. So, the water quantity, water quality, and now since 2006, invasive species, have been really something we’ve had to address.”

Recently, Caddo Lake – which covers parts of Louisiana and Texas – has received national attention. Its battle with salvinia was the focus of a “National Geographic Explorer” television segment. You may watch at https://www. nationalgeographic.com/tv/explorer/. Look for the episode titled “Yellowstone Wolves.”

Caddo Lake was also featured on “CBS News Sunday Morning’s Moment in Nature” segment.

“I think, regionally, many people aren’t that aware of (Caddo Lake),” Overdyke said. “Louisiana is rich in lakes, so people have their pick of them and sometimes forget about Caddo. So, the national spotlight reminds locals what a treasure we have here, and I think it probably draws more national attention so we will have more financial support for our non-profits and more tourism to the Texas side.”

While the Caddo Lake Institute is concerned with the overall well-being of the lake, its focus has been on the Texas side.

“Most of the ecological work to be done so far has been on the Texas side, and that’s where most of our programs have been,” Overdyke said. It benefits the whole lake. The Louisiana side benefits from the work on the Texas side – cleaner water, more water.”

And perhaps, before long, the entire lake will benefit from salvinia-less water.

To learn more about the Caddo Lake Institute, you may visit www. caddolakeinstitute.org.