ACL TEARS

Surgical and non-surgical treatments

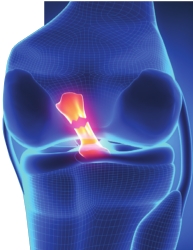

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) connects the femur (thigh bone) to the tibia (shin bone).

It prevents the tibia from sliding forward and rotating excessively. Over 100,000 new ACL tears occur each year in the United States with an estimated impact on health-care costs of $600 million to $1 billion. Females experience ACL

injuries at a higher rate (3:1) than males due to increased laxity of their ligament connective tissues, differences in the bony anatomy of their knees, the alignment of their lower extremities (pelvis to knee to ankle), and sometimes decreased hamstring muscle strength and balance.

The ACL can be torn by stopping suddenly, landing from a jump, cutting or pivoting, or a direct contact injury to the lower leg or knee. Most ACL injuries (around 70 percent) are non-contact sports injuries which most commonly occurin individuals playing soccer, basketball, football or snow skiing.

ACL injuries are diagnosed by physical exam through a finding of laxity of the ACL on stressing the knee called Lachman and pivot shift exams, joint swelling and tenderness. Patients often report feeling or hearing a loud “pop” at the time of injury and afterwards having immediate swelling and instability of the joint. X-rays can diagnose fractures associated with ACL tears, but the diagnosis is usually confirmed with an MRI.

Once

the diagnosis is confirmed, the patient and physician must decide

whether it is best to proceed with non-surgical or surgical treatment.

Non-surgical treatment involves physical therapy to regain range of

motion, strength and as much stability as possible. Braces are often

used for sports or other high demand activities.

Reasons to consider surgical treatment include:

• Preventing damage to the meniscus (soft cartilage pad between the tibia and femur)

•

Preventing damage to the articular cartilage of the knee (firm

cartilage which covers the end of the bone), which would otherwise

increase the chance of getting early-onset arthritis

• Returning stability to the knee for activities of daily living, work demands or sport.

If the decision is made to proceed with ACL surgery, the ACL usually must be rebuilt with a graft (tissue scaffold) because the ligament can usually not be repaired to the bone or to itself. Common graft options to reconstruct the ACL include the patient’s own patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon, hamstring tendons or cadaver (donated) tissue. There are positive and negative aspects of all these graft options, so they should be discussed at length with the physician before proceeding with surgery. It is imperative that range of motion is regained with the assistance of a physical therapist before surgery, or else there is a risk of significant knee stiffness after the ACL surgery.

ACL surgeries today are done with the use of an arthroscope, where the internal contents of the knee joint are viewed on a monitor connected to a camera placed inside the joint. Meniscus and cartilage injuries can also be diagnosed at the same time and repaired as necessary. The torn native ACL tissue is then removed, and then tunnels are drilled into the femur and the tibia to place the ACL graft in the same position as the native ACL was located. The graft is held under tension as it is fixed into place using bio-absorbable or metallic screws, metallic buttons, spiked washers or staples. Special techniques must be used to avoid damage to the growth plates in patients who aren’t yet skeletally mature. Stability of the graft is ensured by pulling on the graft while viewing it arthroscopically. Regional pain blocks are often performed by the anesthesiologist, which help significantly with controlling pain and allowing the majority of these procedures to be performed in an outpatient setting.

Braces and crutches are used while muscle control is regained in the knee and perhaps longer if a meniscus repair or articular cartilage procedure is performed. Physical therapy resumes post-operatively with a step-wise progression of regaining strength, endurance, balance and stability. If a return to competitive sports is desired, the final stages of the therapy program can be tailored to that particular sport. The average time to returning to competitive sports is six months from the date of surgery.

The risk of re-tearing the ACL graft is dependent on the age of the patient at the time of the surgery, type and size of the graft tissue used, sex of the patient and sport played. Overall, the re-tear rate is approximately 2-10 percent in the operative knee and up to 16 percent in the nonoperative knee. Most re-tears occur during the first year after surgery.

Over 80 percent of patients return to some kind of sport following ACL surgery, but the rate to return to the same level of competition is about 60 percent overall.

In order to limit the number of ACL surgeries required, there have been several ACL tear prevention programs developed for coaches and athletes to utilize in their training sessions. Some examples of these include the PEP program (http:// smsmf.org/smsf-programs/pep-program) and Sportsmetrics (http://sportsmetrics. org/). These programs are felt to be more beneficial if athletes start them during early adolescence, prior to when young athletes develop certain habits that increase the risk of an ACL injury. Some studies have shown that these type of prevention programs can decrease the rate of non-contact ACL tears by 30-60 percent.

Dr. Carlton Houtz is an orthopaedic sports medicine surgeon at Highland Clinic Center of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine who routinely performs shoulder replacement procedures. He can be reached at (318) 798-4623, and his office is located at 1455 East Bert Kouns Industrial Loop, Suite 210, Shreveport, LA 71106. His office Web site is www. highlandclinic.com.