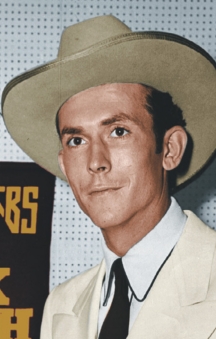

HANK TURNS 100

The Life and Legacy of Shreveport-Bossier’s Adopted Son

In September of 1952, Hank Williams returned to the stage of the Municipal Auditorium in downtown Shreveport to perform once again on the Louisiana Hayride radio program. Having just been unceremoniously fired from the Grand Ole Opry, Hank had jumped at the invitation to return “home” to Shreveport-Bossier and perform once again in the place where he had found fame and success a mere four years earlier.

When Hayride announcer Horace Logan introduced Hank to the crowd upon his return that September night, he was met with raucous cheers. During the introduction, Logan treated Hank like a long-lost son.

“It’s been about two years since you’ve been home, boy,” Logan said. After some friendly banter, Hank announced his song choice for the evening. The crowd roared, and Hank tore into a crowd-pleasing rendition of his hit song “Jambalaya.”

A little more than three months after his boisterous Louisiana homecoming, Hank Williams would be dead – instantly catapulted into the stratosphere of American musical mythology. He died in the early morning hours of New Year’s Day, 1953. His death famously came in the backseat of his babyblue Cadillac en route to a gig in Canton, Ohio.

A little more than three months after his boisterous Louisiana homecoming, Hank Williams would be dead – instantly catapulted into the stratosphere of American musical mythology. He died in the early morning hours of New Year’s Day, 1953. His death famously came in the backseat of his babyblue Cadillac en route to a gig in Canton, Ohio.

The official cause of death was listed as heart failure, an apropos diagnosis for a crooner and blues man whose greatest gift was channeling his brokenness through words and music. The man known as the Hillbilly Shakespeare never saw his 30th birthday.

Hank Williams’ story is unquestionably intertwined with Shreveport and Bossier City. The references to his time in the Ark-La-Tex are constant in the countless historical accounts of Williams’ life. “However, when you travel throughout the Shreveport-Bossier metro area, you will find no murals of Hank Williams, no museums and no statues either. Aside from being honored in the Northwest Louisiana Walk of Stars, there’s hardly a whisper or a hint that one of the most influential musicians in American music history called this area his home for almost a year.”

While Shreveport-Bossier may not yet sufficiently recognize its own significance in Hank’s story, Hank aficionados certainly do. In the Hank Williams Museum in Montgomery, Ala., Shreveport and Bossier City cities are mentioned in writing no less than 39 times.

The story of Hank Williams in Shreveport-Bossier is not the stuff of myths or conjecture. It is instead the very real story of a fledgling star who found a chance at stardom in a new city and who later in life returned to that city – one of the few places where he had been happy during his short, tumultuous life.

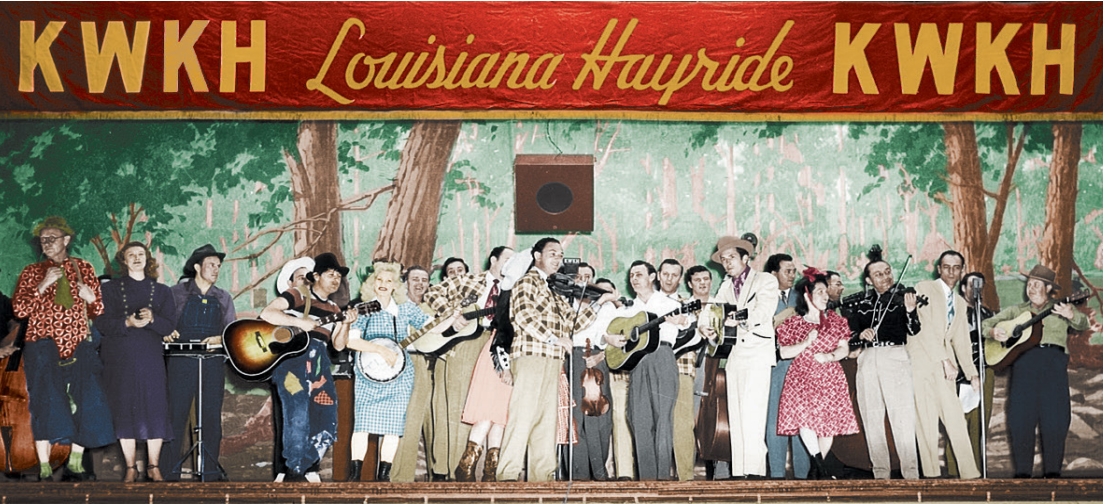

When Hank Williams first came to Shreveport from Alabama in the summer of 1948, he was almost 25 years old. He had agreed to appear on KWKH’s Louisiana Hayride radio program – a program that at that time was only four months old. But Hank needed a chance to prove himself, and the Hayride was the perfect platform. Broadcast on 50,000-watt KWKH, anyone who appeared on the Louisiana Hayride was guaranteed to reach a wide audience and, with luck, receive an invite to the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tenn. – the goal of every country musician trying to “make a name.” The Hayride’s propensity to do just that for countless singers over its run earned it the moniker “Cradle of the Stars.” Hank would be the very first major star to emerge from that cradle.

On Aug. 7, 1948, Hank appeared on the Louisiana Hayride for the first time. He sang a song called “Move It On Over” – a song released a year earlier on the MGM label. Hank was the fifth performer in the 8-8:30 segment.

His appearance on the Louisiana Hayride resulted in a slow-moving freight train of stardom that would quickly become an out-of-control locomotive. In the meantime, as fame loomed, Hank had to begin the real work of making a life in Shreveport-Bossier. Hank’s interactions around the city were those of any young musician trying to make their way in the world: renting an apartment, picnicking at the lake, playing lackluster gigs, buying a first home, and even enduring marital strife.

Hank Williams performs alongside other notable musicians on the stage of the famous Louisiana Hayride.

Hank first rented a garage apartment located at 4802 Mansfield Road in Shreveport. (Coincidentally, the property’s current caretaker shares a birthday with Hank Williams.) Hank’s band from Alabama joined him. But because they were new musicians in town, work was sparse. Hank’s low-paying gigs could not fund an entire band. Needing to make money, most band members eventually returned to Alabama.

One of the more noticeable characteristics of the Mansfield Road property is a set of railroad tracks directly across the street. The railroad tracks’ proximity to where Hank first rested his head in Shreveport leaves historians to ponder just how much the constant blowing of a lonesome train horn in the passing night might have later inspired Hank’s famous line “the midnight train is whining low/I’m so lonesome I could cry.”

Shreveport resident Ronnie Crawford recalls a Hank Williams story from Mansfield Road shared by his father. The Crawfords owned Kickapoo Plaza Courts and Café #3 – a restaurant, hotel and service station at the corner of Mansfield Road and Hollywood Avenue. At the time, according to Crawford, that address was at the edge of town.

“It was sort of the last outpost for a long time going toward Mansfield,” Crawford said.

“You might not like the song, but when it gets so hot that I walk off the stage and throw my hat back on the stage and the hat encores, that’s pretty hot.”– Hank WilliamsAccording to Crawford’s father, Hank was known to pop into Kickapoo #3 to eat at the restaurant, which sat a mere half-mile from his Mansfield Road address. Ronnie Crawford was too young to remember Hank, but later, he remembered meeting Hayride stars Johnny Horton and Faron Young.

Early in his time on the Hayride, Hank received sponsorship from the Shreveport Syrup Company to promote Johnnie Fair Syrup. Hank peddled syrup while performing on an early morning radio show broadcast on KWKH.

The studios were located at 509 Market St. in downtown Shreveport. Labeling himself “The Ol’ Syrup Sopper,” many of these performances were recorded. In one recording, Hank greets the morning crowd with a familiar down-home folksiness that his fans would come to love.

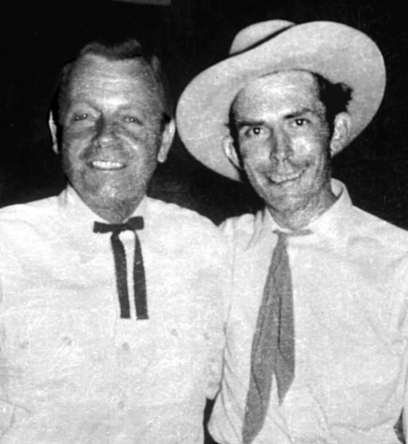

Hank with Governor Jimmie Davis.

“Now, friends, I know all of you can recall when you were kids and what a treat it was to get that good syrup and bread and meat for breakfast,” Hank said. “Now folks have sort of gotten away from using syrup like they used to, but it’s always been one of my favorite sweets – especially that fine Johnnie Fair Blue Ribbon Cane Flavor.”

Between radio appearances, Hank frequented a 24-hour diner on Market Street called the Bantam Grill. The grill was directly across the street from the KWKH studios. In the book “Still in Love with You: The Story of Hank and Audrey Williams,” Hank’s stepdaughter, Lycrecia, wrote the following:

“Between shows [Hank] spent time at the Bantam Grill, which he called ‘the beanery.’ Murrell Stansell, who owned and operated the grill, remembers Daddy wasn’t too sociable at that time of day and would sit for long periods on a stool at the counter just drinking coffee and not talking to anyone.”

Hank’s favorite way to pass time at the Bantam Grill was playing the gambling pinball machine. Recalled Stansell, “He’d be here playing my pinball table, and his band would have to pull him away to get up to the studio on time.”

The Bantam Grill is now long gone, and in its place is the Regions Tower – the tallest building in Shreveport.

Eventually, Hank moved across the Red River to Bossier City. When he joined the Shreveport Music Union on Feb. 4, 1949, Hank listed his home address as 1029 Saint Charles St. in Bossier City.

Around that same time, Hank’s musical fortunes would take a dramatic turn for the better. The main catalyst for this explosion was a recycled pop tune called “Lovesick Blues,” which Hank started singing early in his tenure at the Louisiana Hayride. The Hayride fans went wild over the song, offering Hank an early harbinger of its possible commercial value. A Shreveport Times article noted, “Capacity crowds at the Hayride nearly tear the house down for encores of ‘Lovesick Blues.’”

According to Hank’s biographer, Colin Escott, recording “Lovesick Blues” was an afterthought – a last-minute addition to a three-hour recording session in Cincinnati. Producer Fred Rose was not a fan of the song, allegedly describing it as “the worst damn thing I ever heard.” Hank’s session mates agreed with Rose. The discussion over whether to record it became heated, recalled mandolinist Clyde Baum. During the argument, Baum heard Hank tell Fred Rose, “You might not like the song, but when it gets so hot that I walk off the stage and throw my hat back on the stage and the hat encores, that’s pretty hot.”

The song ended up getting recorded, and Hank’s intuition regarding “Lovesick Blues” turned out to be right. The song was an instant hit. In the first 17 days after its February release, the song that Fred Rose didn’t want to record sold more than 48,000 copies. One month later, in March, the song showed up on the country charts.

That same month – March of 1949 – the Williams family purchased a new home at 852 Modica St. in Bossier City. Hank, his stepdaughter, Lycrecia, and his spitfire wife, Audrey – who was seven months pregnant with Hank Jr. at the time – settled into their new home. The house, coincidentally, was just down the street from Hank’s future wife, Billie Jean. Years later, the house on Modica Street would fall into disrepair. In 2017, the house was purchased by a rock-and-roll memorabilia collector named Stephen M. Shutts, who dismantled the house one piece at a time. In turn, Shutts sold the remnants of the house to Kid Rock. Currently, the pieces of Hank Williams’ Bossier City house are somewhere in Tennessee.

The first half of 1949 was a whirlwind for the Williams family. They had moved into their new Bossier City home in March. Two months later, on May 7, 1949, “Lovesick Blues” became America’s number one country song. Hank’s friend and Louisiana Hayride legend, Tillman Franks, delivered the good news to him. In the biography “I Saw the Light: The Story of Hank Williams,” Tillman Franks recalled Hank’s reaction to hearing the news.

“Hank was eating at the Bantam Grill,” Franks said. “I’d bought Billboard at the newsstand and ‘Lovesick Blues’ had just gotten to number one. I walked in and showed it to him. It shook him up pretty good. He just sat there silent for the longest time. He realized what that was.”

Three weeks later – on May 26 – Hank and Audrey welcomed Hank Jr. into the world. Then, in June, the whirlwind continued. Hank finally got the long-awaited phone call inviting him to join the Grand Ole Opry. From there, Hank’s life became even more frenetic, spending time in Nashville and touring constantly. He performed regularly on the Grand Ole Opry and made several appearances on the new medium of television. In a span of three years, Hank’s place in the pantheon of American music was solidified as he ascended to the highest levels of fame.

But Hank’s life – not just his career – was a shooting star. As quickly as he rose to fame, his health began to fade. Burdened by worsening alcoholism and the meddling of a controversial doctor named Toby Marshall, Hank’s health and career took a downward trajectory. The coup de grace of Hank’s time in Nashville was his firing from the Grand Ole Opry after missing too many appearances.

On Sept. 24, 1952, Hank Williams signed a new, three-year contract with the Louisiana Hayride, eternally solidifying Shreveport-Bossier’s role as bookends in the rise and fall of Hank Williams.

After his marriage to Audrey Williams ended in an ugly, public divorce, Hank married a Bossier City local named Billie Jean Jones Elshliman.

They had met previously in Nashville while she was dating country singer Faron Young. One of the very first things they chatted about was how they coincidentally both had lived on the same street in Bossier City – 560 miles away.

They had three weddings. The official ceremony was performed on Saturday, Oct. 18, 1952, in Minden, La., by Justice of the Peace P.E. Burton. The next day, the new Williams couple held two ticketed “weddings” in New Orleans. After the wedding, Hank and Billie Jean returned to the Ark-La-Tex and moved into a house at 1346 Shamrock St. in Bossier City. This address is listed on an Oklahoma Biltmore hotel receipt on display at the Hank Williams Museum in Montgomery.

The result of Hank’s whirlwind romance and two-and-half-month marriage to Billie Jean would result in lawsuits and legal quagmires that took years to play out. (Billie Jean married country singer Johnny Horton after Hank’s death.)

During the last few months of 1952, Hank began a downhill slide. His alcoholism was worsening, and he was in and out of the Highland Sanitarium in Shreveport in attempts to stay sober. On Dec. 11, Hank pulled IVs out of his arm, walked out of the sanitarium and headed to downtown Shreveport, where he was arrested for public drunkenness.

To add another layer to his torment, Hank was also addicted to painkillers – a result of tempering the chronic pain from spina bifida and a back injury he received after being thrown from a horse back in Nashville.

Watching his decline, even Hank’s friends doubted his ability to overcome his alcoholism. Even longtime Hank supporter Horace Logan described Hank at that time of his life as “a slobbering drunk.”

Later that month, on Dec. 19, Hank pulled himself together enough to perform for a sold-out crowd at the Skyline Club in Austin, Texas.

No one there knew they were witnessing Hank Williams’ last public performance. Bandmate Tommy Hill recalled that it was one of the best Hank Williams shows he’d ever seen. The 8 p.m. gig, which was only supposed to last about an hour, went until almost 1 a.m. Hank even sang some of his favorite gospel songs.

Immediately after the gig was over, Hank and his entourage drove through the night back to Shreveport, where Hank checked into the hospital to be treated for pneumonia. The next day, citing that Hank was “very obviously physically ill,” Horace Logan granted Hank a leave of absence from his Hayride obligations, hoping he would finally find lasting treatment for his alcoholism.

Sadly, that treatment would never come.

Hiram “Hank” Williams died 12 days later in the back seat of his Cadillac. Poetically, within days of his death, Hank’s latest song, “I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive,” shot to number one on the Billboard charts.

Hank WIlliams with band, the Drifting Cowboys.

Hank’s legacy speaks for itself. He was among the first three inductees into the Country Music Hall of Fame. He is also enshrined in the Songwriters Hall of Fame. In 1987, he was even inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. This begs the question: Why is a country music star honored in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

The reason is simple: Some historians argue that Hank Williams was the first rock-and-roll star. He had learned to play music from a black street blues musician named Rufus “Tee-Tot” Payne. Later, Hank seamlessly melded country and blues together in the song “Move it On Over,” a song whose arpeggiated melody line and blues progression are hauntingly similar to Bill Haley’s 1954 hit “Rock Around the Clock.” Hank’s music,

charisma, looks, crossover appeal and largerthan-life aura helped him reach levels of fame no American entertainer had known.

In other words, he was a rock star.

Beyond the rock-star nature of his life and endless accolades is Hank’s immeasurable influence on America and its music. A whole generation of future rock-and -roll stars were watching Hank’s meteoric rise during the most impressionable years of their own lives, and Hank was creating the blueprint they would all use to create an entirely new genre of music we call rock and roll.

When historians examine the brief, influential life of Hank Williams, there are consistent themes. He was indeed charismatic, troubled, heartbroken and an alcoholic.

But these very real attributes often enabled Hank to connect with his fans’ very real joys and troubles. And they reciprocated their appreciation by buying albums. In a little over five years after his first record deal, Hank sold an estimated 10 million albums.

Despite the brevity of his career, Hank recorded an astonishing 225 songs. In the years since, Hank’s songs have been covered by everyone from Ray Charles to Tony Bennett, Norah Jones, Harry Connick Jr. and countless others. In addition to covers, Hank’s life has inspired more than 75 songs about him. Among them are “Midnight in Montgomery” by Alan Jackson, “The Ride” by David Allen Coe, “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” by Waylon Jennings, and “The Night Hank Williams Came to Town” by Johnny Cash. Hank Williams Jr. himself alluded to his father’s troubled life in the classic bar singalong “Family Tradition.” In addition to songs, four feature films and countless documentaries have been made about the life of Hank Williams. One of those films, “I Saw the Light,” starring Tom Hiddleston, was fittingly filmed in Shreveport-Bossier. The number of books written about Hank Williams could fill a library.

On Sept. 17, 2023, Hank Williams fans worldwide will celebrate what would have been Hank’s 100th birthday. Shreveport and Bossier City – for their role in the story of Hank Williams – will also honor the momentous occasion. A singalong is planned on the steps of the Shreveport Municipal Auditorium on Sunday, Sept. 17, at 2 p.m.

The railroad tracks’ proximity to where Hank first rested his head in Shreveport leaves historians to ponder just how much the constant blowing of a lonesome train horn in the passing night might have later inspired Hank’s famous line “the midnight train is whining low/I’m so lonesome I could cry.”

For Shreveport-Bossier, the story of Hank Williams is the story of what might have been. If he had lived longer, would he have stayed in Shreveport? Would he have lived here till his dying day? Would he have been buried here? And perhaps the most tantalizing thought: If he had lived through 1955, Hank might have shared the Louisiana Hayride stage with both Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash – a cataclysmic musical collision that would have left even the most articulate music historians flailing for description.

But the might-have-beens and what-ifs will have to remain. Unlike many great artists who outlived their own legend, Hank did not. By dying young and avoiding the conundrum of rock-androll, Hank’s music and legacy remain that of an influential predecessor. Hank’s ascendence was a warning shot across the bow of American music.

This rise would foreshadow the revolutionary wave of cultural changes barreling toward the nation in the mid-1950s.

As such, Hank’s legacy is evident: a musical juggernaut whose tortured life and gentle heart paved the path for all subsequent musicians and whose influence will live on for generations to come. And as Hank’s story will undoubtedly never fade, Shreveport-Bossier will be eternally regarded with a simple and meaningful line in Hank’s epitaph, spoken best by his biographer Colin Escott:

“In a lot of ways, the year that Hank spent in Shreveport was the happiest of his life.”

Hank and his stepdaughter, Lycrecia, pose for a photo next to the star’s famous Cadillac.