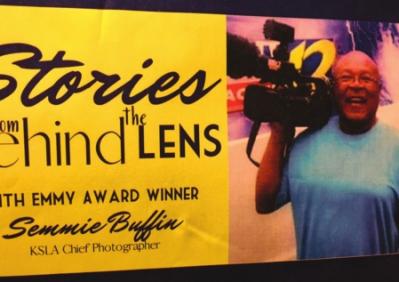

Semmie Buffin: A Look Back

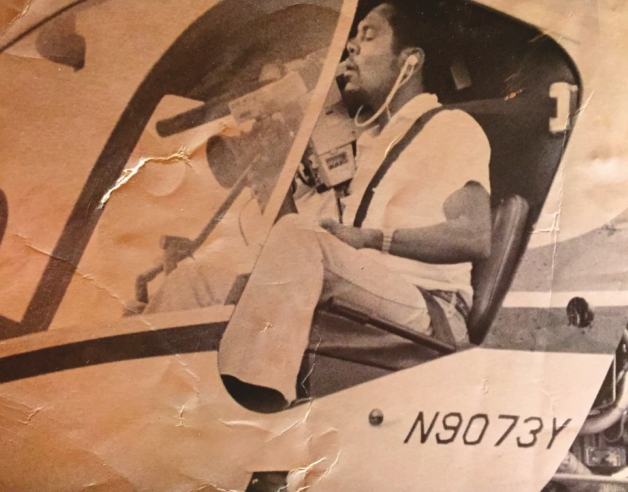

The man behind the camera takes a seat

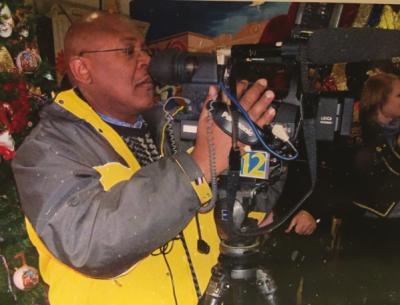

Semmie Buffin went to work for KSLA TV in 1974. In those days, the local CBS affiliate was locally owned by the people who had shepherded it onto the air in the early 1950s. Fast forward 46 years, and many things about the station were vastly different, but one thing remained constant: Semmie Buffin.

Born in 1953 and raised in north Caddo Parish in the little town of Belcher, Buffin went to North Caddo High School in Vivian. There he discovered a love of photographing football and basketball highlights for the team coaches. “I was always interested in cameras,” he admitted.

When his future wife graduated from high school, she worked as a receptionist at the NBC affiliate, KTAL.

When his future wife graduated from high school, she worked as a receptionist at the NBC affiliate, KTAL.

“When I graduated in 1972, I had no idea where I was going, what I was going to do. [Future Mrs. Buffin, Bert] said, why don’t you come to Channel 6, they’ve got a news department and you’ve got camera guys running around here covering the news. I’m like: Who’s going to give me a job? I have no experience except for the little video I’ve been shooting for football games.”

But, he went, interviewed with news director Stan Wyatt and got a job, but in the mailroom as a clerk. “That got my foot in the door. Once I got my foot in the door and saw the news operation, found out what was going on, I asked Jim Cato, who was in the news department, if he would train me. He gave me a Bell & Howell wind-up, 16mm camera. He then gave me an Auricon, a sound camera with a suitcase full of amplifiers and cords and everything. He trained me. And once he trained me, the rest is history.”

Buffin worked at KTAL for two years until KSLA’s legendary news director and prime anchorman, Don Owen, contacted him asking if he’d be interested in working at Channel 12. “I said sure because that’s where my loyalty was because my parents watched Channel 12 all the time. I grew up watching that station, so, sure, I wanted to work at the number one station.

“So, he brought me over there, and I started to work in 1974.”

Owen asked Buffin to take over the position of chief news photographer, giving him hiring and firing responsibilities and budget oversight. “Man, I had no experience, so I told him yes because he had faith in me to do it.”

That faith was rewarded over the next 46 years through multiple sea-change developments throughout the station and the television industry. While changes swirled around him, the one constant was Semmie Buffin. He worked with local legends over those four decades. Besides Owen, he worked with Mike Staggs, Tom Erwin, Wray Post, Dennis Bounds, Margaret Larsen, Roseanne Colletti and countless others. The personnel came and went, but so, too, did the media. The celluloid film cameras on which he honed his craft gave way to electronic image gathering devices that recorded video on magnetic tape. “Going from film to videotape, from ¾ inch to beta to ½ inch to disk to mini DV. Suddenly, we went to digital. I think digital was the most difficult. A lot of photographers ended up quitting because they just couldn’t grasp it,” Buffin said.

What once required large cases of wiring, equipment, amplifiers and microphones morphed into smaller and smaller devices. Film processing and manual splicing of film to edit stories became electronic. What used to take hours to achieve could almost be done instantaneously.

Despite all the change, Buffin rolled with the tide. Eventually, all things come to an end, and his active television career was no different. Still hale and hearty, Buffin saw the time was right to think about spending more time with his wife, his two grown daughters, Ashley and Alana, and his two grandchildren.

Despite all the change, Buffin rolled with the tide. Eventually, all things come to an end, and his active television career was no different. Still hale and hearty, Buffin saw the time was right to think about spending more time with his wife, his two grown daughters, Ashley and Alana, and his two grandchildren.

“I was going to retire in March [2020] on my birthday, but when the coronavirus hit, I said, oh, gee, I cannot leave my coworkers with this. We were trying to strategize how we were going to cover the news. How were we going to keep from catching the virus ourselves? How were we going to keep ourselves safe as well as trying to work in this crazy world? I couldn’t leave them. I decided to stay.”

He stayed on with the help of a lot of Lysol, a lot of masks, a lot of rubber gloves. “I was going to go until the end of [2020], but I said, I’m going to give myself an early Christmas gift because I think I deserve it. I had seen enough.”

Buffin said, “There were four times when I got depressed while doing this. Number one was the Cedar Grove riots. Number two was 9/11. Number three, [the COVID-19] pandemic. Number four, all the shootings we’ve been responding to. I remember covering four shootings in one night. You get immune to it. It’s ‘where am I going to go to cover a shooting today?’ Most of these shootings are in the broad daylight. That was so depressing.”

The pandemic also created a disconnect among his coworkers. Many worked from home. The few who came to the station were socially distant. The close-knit family environment Buffin had grown up in was disappearing.

“I guess you could say I worked from home, but I worked out of my vehicle. We would have to go and park and wait for the assignment. Check the 911 [website] and see what was going on and respond to it. The toughest thing is finding somewhere to eat and eat in your vehicle, and finding a place to use the bathroom because most places were closed. That was every day, Joe, and it just got depressing when you don’t go to an office.”

Looking

back on a career that spans four decades in a business where personnel

is constantly changing, some things naturally stand out. But despite the

things he’s covered, like local visits of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford

and George Bush on 9/11, one of his most memorable assignments was to

cover a guy opening his first chicken restaurant in Shreveport.

Looking

back on a career that spans four decades in a business where personnel

is constantly changing, some things naturally stand out. But despite the

things he’s covered, like local visits of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford

and George Bush on 9/11, one of his most memorable assignments was to

cover a guy opening his first chicken restaurant in Shreveport.

“I was working at Channel 6 at the time. They said you’re going to interview the colonel. I’m like, who is Colonel Sanders?

“I get down there, and I’m shooting film, mind you, and I see this white guy standing there, dressed in all white. The only thing black on him was the little string tie that he was wearing. And I’m trying to figure how I can get the exposure right on this. He’s dressed in all white. He’s out in the daylight. The building behind him is white. Oh, my goodness, I must have taken 15 meter readings. You know what, I nailed it. I got it just right, F16.

“The very first thing I asked him, and he said no one had ever asked him that before, what was his favorite part of the chicken? You know what he told me? The wingtip. Not the wing, but the wingtip.

“He told me he was going to sell chicken out of a bucket. In my mind, I’m going, yeah, right. But did he ever prove me wrong. He was a real nice guy, as nice as you could ever want to be.”

On a personal note, I worked with Semmie Buffin over the years. His assessment of Col. Harlan Sanders could just as easily apply to him. He is a real nice guy, as nice as you could ever want to be.

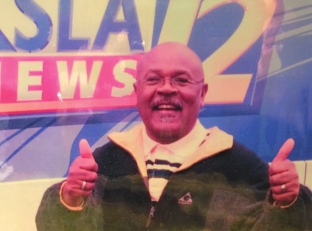

Buffin credits his longevity to his KSLA family. “Those people, as soon as I walked through the door, Mike Staggs, Tom Erwin, Wray Post, all those older guys that blazed a trail for me, believed in me. That’s why I’ve been there for so many years because of what I learned from them. Mostly it was respect. Yes, sir. No, sir. And a work ethic that doesn’t even exist today.

“Through the years, [KSLA] afforded me to travel. Afforded me to have some things that I don’t think I would have been able to afford. The KSLA family are just good people.”

And so, Semmie Buffin, are you.