Killer Dad

WOMAN COPES WITH WITNESS PROTECTION FALLOUT

Someone in the Witness Protection Program could live right next door.

I was on a Zoom for Crime Con when Jackee Taylor of the "Relative Unknown" podcast spoke. I about fell out of my chair when she said she had been in witness protection and now discusses it, saying her dad, Butch Crouch, was placed in Shreveport.

Crouch, 73, ended up marrying and killing his second wife, age 85, and her son, Ed, 61, who had brain cancer, in East Texas and setting the home on fire, then committing suicide. He was found on July 8, 2013, with no shirt and his pants unzipped in a blue Jaguar. The bodies were inside the dwelling in the Texas heat for three days.

There had been a sign on the door that he was in Louisiana, and later neighbors realized they were dead. "You don't always know people," a neighbor said. They knew Paul Dome (his witness protection name) well but knew nothing about Butch Crouch, his real name. It was a secret even from his wife.

Jackee Taylor comes from a troubled background, to say the least. She hosts the "Relative Unknown" podcast, where listeners learn more of her story. Her father, Butch Crouch, also known as Paul Dome, was what can be called a career criminal, involved in a string of crimes ranging from theft to attempted murder, homicide, and even prison time.

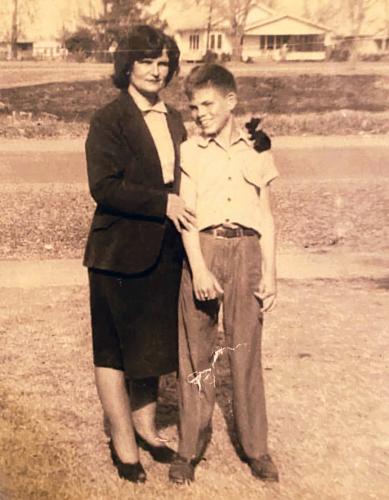

Born to an unwed, deaf, mute woman named Verline Williams in Shreveport in 1940, Clarence "Butch" Addie Crouch bounced around orphanages and care homes during his--early years. His mother remarried to get custody of Butch, but he stayed in trouble; finally, he ran away at age 14, only occasionally returning for short visits to his mother.

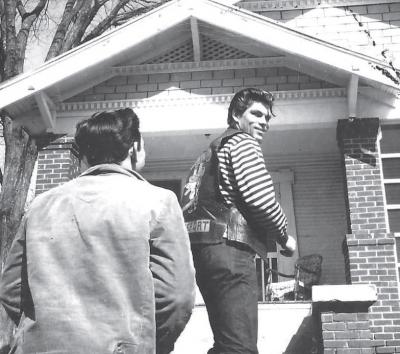

His criminal career featured arrests for burglary, theft, assault, and included a five-year stint in Texas' Huntsville Prison, where he acquired a love for motorcycles. Upon his release, he became one of the founding members of the Bandidos motorcycle gang. Eventually, he was recruited by Sonny Barger, founding member of the Hell's Angels Oakland, Calif., chapter, to start chapters of Hell's Angels around the country before ending up in Cleveland, Ohio.

In Cleveland, Crouch was involved in murder, prostitution, theft, drug trafficking and sex crimes. Gang wars were common during this part of Crouch’s career, and over the next 10 years, he would be investigated on suspicion of rape, narcotics and assault charges.

Facing a

lengthening list of criminal charges, Crouch offered to turn state’s

witness against the Hell’s Angels in 1981. He was placed in the Witness

Protection Program and given the new identity of Paul Dome.

Facing a

lengthening list of criminal charges, Crouch offered to turn state’s

witness against the Hell’s Angels in 1981. He was placed in the Witness

Protection Program and given the new identity of Paul Dome.

Crouch/Dome’s first wife, Mary, took their children, including Jackee, and moved to Florida to escape the violence Crouch’s life had brought into their lives. When she was 8 years old, Jackee and her family were whisked away by Witness Protection, eventually ending up in Billings, Mont. Crouch would drop in for a few brief stints in Montana, but Jackee’s mother later filed for divorce. She took the surname Taylor reportedly because of her admiration for Elizabeth Taylor.

Jackee was barely 8 years old, and unable to say goodbye to friends. She remembers sitting in her room and writing her new name over and over again in a notebook, practicing. Jackee Taylor. Jackee Taylor. Jackee Taylor.

Cut off from Crouch, Mary ran into serious financial problems. Eventually, she lost custody of Jackee, who was put into a state group home when she was 16 years old. In foster care, Jackee had difficulty proving her identity because she had no official documents.

While his first family eked out a living in Montana, Crouch bounced around Arkansas and Louisiana before happening upon Vivian Greer. The latter had been looking for someone to work on her house in exchange for room and board. By this time, Crouch had left the witness protection program, intending to fashion a new life. The two married shortly after that and returned to East Texas, Crouch’s old stomping grounds. They settled in Avinger.

As the years passed, Jackee became obsessed with finding out about her father. Her own children were denied medical coverage because Jackee still had the official identity issues from being in the witness protection program. Frustrated, she went public, talking to the Billings (Mont.) Gazette; she described problems like establishing her identity for passports or even a marriage license because of her witness protection experience.

She eventually traveled to Louisiana in search of her father’s sister in Campti. While there, she learned that her grandfather had physically abused her father. Her aunt told her Crouch lived an hour and a half away and was a crippled old man with no teeth.

Despite years of resentment, Jackee felt the animosity wane when she visited her father. She accepted her change of heart because “that’s my daddy,” she said.

Following

her visit, Crouch and Jackee started corresponding. Crouch attempted to

get a Social Security disability to help with his medical issues since

Witness Protection does not provide medical coverage. Crouch filed for

his medical records under the Freedom of Information Act.

Following

her visit, Crouch and Jackee started corresponding. Crouch attempted to

get a Social Security disability to help with his medical issues since

Witness Protection does not provide medical coverage. Crouch filed for

his medical records under the Freedom of Information Act.

Crouch’s story came to an end in 2013, when his body was found dead by his own hand after killing his second wife and his stepson. A week after his death, Jackee came back to the area to retrieve Crouch’s ashes. She sprinkled them on his favorite fishing spot.

She also found a trunk that contained items from Butch Crouch’s life. In the trunk was a letter from his second wife telling Crouch he had to decide if alcohol was more important to him than she was. Taylor found a lot of odds and ends, documents, news articles and the makings of a manuscript. It contained 475 single-spaced pages which bore the title, “Hate and Discontent.” Jackee has locked it away.

Eventually, she returned to Cleveland to return her father’s Hell’s Angels patches, despite rumors that the Angels had been plotting her death since she was 7 years old. She walked into the clubhouse to give the patches back, where she was told by gang members they would never have hurt Crouch’s family. She said it was a relief, and she felt a sense of closure. She could move forward with her own life and not look back at her father’s.

For now, she’s taking her own Witness Protection Program experiences to fight for proper medical coverage, identification assistance and mental health care. According to Taylor, there needs to be a special advocate for each child in the program. She also said there must be a grave danger to the child’s life before putting him or her into witness protection. She plans to testify before a Senate Judiciary Committee on the issues. In her family’s case, she said, “[Witness Protection] placed three little children with a serial killer.”

What she lacks in family, friends have made up for. “If I had anything good to say about the marshalls is the picked the right town,” she said. “Ilove billings.” She serves dinner at the Montana Rescue Mission on Christmas Eve snd has volunteered with Hospice. She starting a 501C3 to help people in crisis.